Published by The Associated Press, November 2024 (link aquí)

LIMA (AP) – Sadith Silvano’s crafts are born from ancient songs. Brush in hand, eyes on the cloth, the Peruvian woman paints as she sings. And through her voice, her ancestors speak.

“When we paint, we listen to the inspiration that comes from the music and connect to nature, to our elders,” said Silvano, 36, from her home and workshop in Lima, Peru, where she moved two decades ago from Paoyhan, a Shipibo-Konibo Indigenous community nestled in the Amazon.

“These pieces are sacred,” she added. “We bless our work with the energy of our songs.”

According to official figures, close to 33,000 Shipibo-Konibo people inhabit Peru.

Settled in the surroundings of the Uyacali river, many relocated to urban areas like Cantagallo, the Lima neighborhood where Silvano lives.

Handpainted textiles like the ones she crafts have slowly gained recognition. Known as “kené,” they were declared part of the “Cultural Heritage of the Nation” by the Peruvian government in 2008.

Each kené is unique, Shipibo craftswomen say. Every pattern speaks of a woman’s community, her worldview and beliefs.

“Every design tells a story,” said Silvano, dressed in traditional clothing, her head crowned by a beaded garment. “It is a way in which a Shipibo woman distinguishes herself.”

Her craft is transmitted from one generation to another. As wisdom is rooted in nature, the knowledge bequeathed by the elders connects younger generations to their land.

Paoyhan, where Silvano was born, is a flight and a 12-hour boat trip away from Lima.

In her hometown, locals rarely speak languages other than Shipibo. Doors and windows have no locks and people eat from Mother Nature.

Adela Sampayo, a 48-year-old healer who was born in Masisea, not too far from Paoyhan, moved to Cantagallo in the year 2000, but says that all her skills come from the Amazon.

“Since I was a little girl, my mom treated me with traditional medicine,” said Sampayo, seated in the lotus position inside the home where she provides ayahuasca and other remedies for those ailing with a wounded body or soul.

“She gave me plants to become stronger, to avoid getting sick, to be courageous,” said Sampayo. “That’s how the energy of the plants started growing inside me.”

She, too, conveys her worldview through her textiles. Though she does not paint, she embroiders, and each thread tells a tale from home.

“Each plant has a spirit,” said the healer, pointing to the leaves embroidered in the cloth. “And medicinal plants come from God.”

The plants painted by Silvano also bear meaning. One of them represents pure love. Another symbolizes a wise man. One more, a serpent.

“The anaconda is special for us,” Silvano said. “It’s our protector, like a god that cares for us and provides food and water.”

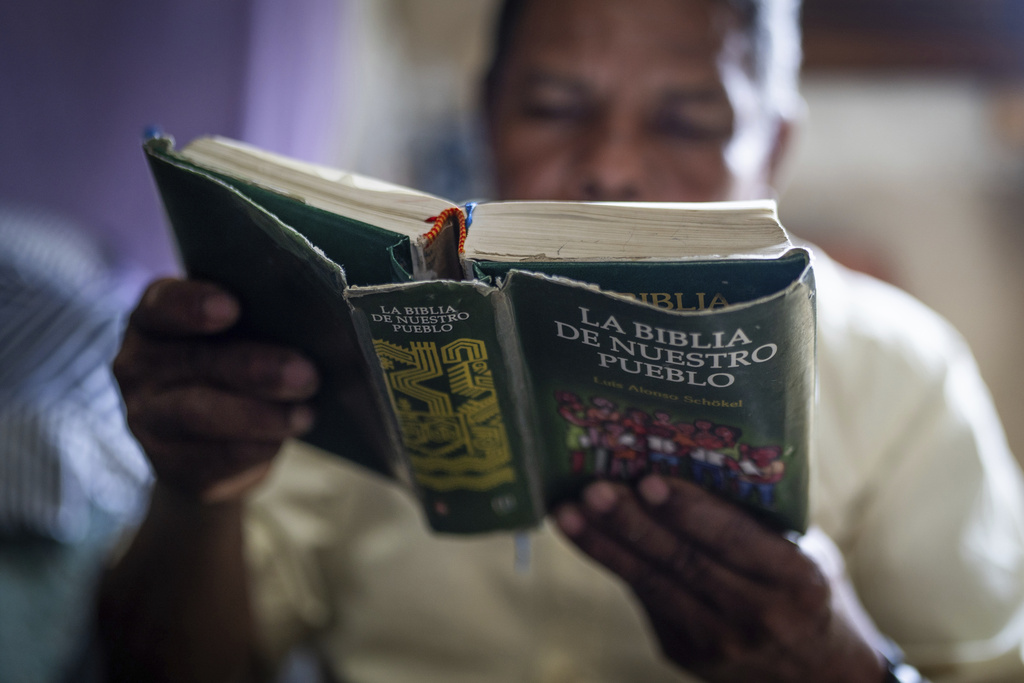

In ancient times, she said, her people believed that the sun was their father and the anacondas were their guardians. Colonization brought a new religion — Catholicism — and their Indigenous worldview was diluted.

“Nowadays we have different religions,” Silvano said. “Catholic, evangelical, but we respect our other beliefs too.”

For many years, after her father took her to Lima hoping for a better future, she yearned for her mountains, her clear sky and her time alone in the jungle. Life in Paoyhan was not precisely easy, but from a young age she learned how to stay strong.

Back in the 1990s, Amazonian communities were affected by violence from the Shining Path insurgency and illegal logging. Poverty and sexism were also common, which is why many Shibipo women taught themselves how to navigate their anguish through the heartfelt music they sing.

“When we encounter difficult times, we overcome them with our therapy: designing, painting, singing,” Silvano said. “We have a song that is melodic and heals our soul, and another one that is inspiring and brings us joy.”

Few Shipibo girls are encouraged to study or make a living of their own, Silvano said. Instead, they are taught to wait for a husband. And once married, to endure any abuse, cheating or discomfort they may encounter.

“Even though we suffer, people tell us: Take it, he’s the father of your children. Take it, he is your husband,” Silvano said. “But deep inside, we are wounded. So what do we do? We sing.”

The lesson is taught from mothers to daughters: If you hurt at home, grab your cloth, your brush and leave. Go far away, alone, and sit. Connect with your kené and paint. And while you paint, sing.

“That’s our healing,” Silvano said. “Through our songs, our kenés, we are free.”

In the workshop where she now works and raises her two children on her own, Delia Pizarro crafts jewelry. She, too, sings as she creates birds out of colorful beads.

“I didn’t use to sing,” Pizarro said. “I was very submissive and I didn’t like to speak, but Olin, Sadith’s sister, told me, ‘You can do this.’ So now I’m a single mother, but I can go wherever I want. I know how to defend myself and fight. I feel valued.”

The figures in the products they craft for sale are varied. Aside from anacondas, they like to depict jaguars, which represent women, and herons, which were treasured by the elders.

A Shipibo textile can take up to a month and a half to be completed. Materials required to craft it — the cloth, the natural pigments — are brought from the Amazon.

The black color used by Silvano is extracted from a bark tree that grows in Paoyhan. The cloth is made of local cotton. The mud used to set the colors comes from the Uyacali river.

“I like it when a foreigner comes and leaves with something from my community,” said Silvano, touching one of her freshly painted textiles to bless it for a quick sale.

She said that her people’s crafts were barely known when she and her father first arrived in Lima 20 years ago. But in her view, things have now changed.

In Cantagallo, where around 500 Shipibo families have settled, many make a living selling their crafts.

“My art has empowered me and is my loyal companion,” Silvano said. “Thanks to my mother, my grandmother and my sisters, I have a knowledge that has allowed me to open doors.”

“Here’s the energy of our children, our ancestral world and our community,” she added, her textiles still between her hands. “Here’s the inspiration from our songs.”

____

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.