Published by The Associated Press, June 2025

God’s message didn’t immediately make sense to pastor José Luis Orozco. But when U.S. efforts resulted in his release from a Nicaraguan prison a few months later, everything became clear.

“The Lord had told me: ‘Don’t be afraid, José Luis. A wind will blow from the north, your chains will break and the doors will open,’” the pastor said from his new home in Austin, Texas.

By September 2024, he had spent nine months behind bars. With 12 other Nicaraguan members of the Texas-based evangelical Christian organization Mountain Gateway, he faced charges like money laundering and illicit enrichment. Just like them, other faith leaders had been imprisoned during a crackdown that organizations, such as Human Rights Watch, have said are attacks on religious freedom.

Orozco thought his innocence would eventually surface. So when the U.S. government announced that it had secured his release along with other political prisoners, he wasn’t completely surprised.

“That’s when I understood,” the pastor said. “God was telling me he would act through the United States.”

In the hours following the announcement, 135 Nicaraguans were escorted to Guatemala, where most sought paths to settle in other countries.

Why did Nicaragua imprison religious leaders?

Tensions between President Daniel Ortega and Nicaraguan faith leaders began in 2018, when a social security reform sparked massive protests that were met with a crackdown. Relations worsened as religious figures rejected political decisions harming Nicaraguans and Ortega moved aggressively to silence his critics.

Members of Catholic and Evangelical churches have denounced surveillance and harassment from the government. Processions aren’t allowed and investigations have been launched into both pastors and priests. CSW, a British-based group that advocates for religious freedom, documented 222 cases affecting Nicaraguans in 2024.

“Religious persecution in Nicaragua is the cruelest Latin America has seen in years,” said Martha Patricia Molina, a Nicaraguan lawyer who keeps a record of religious freedom violations. “But the church has always accomplished its mission of protecting human life.”

Spreading the gospel

Orozco was the first member of his family to become evangelical. He felt called to the ministry at age 13 and convinced relatives to follow in his footsteps. He began preaching in Managua, urging different churches to unite.

His experience became key for Mountain Gateway’s missionary work. Founded by American pastor Jon Britton Hancock, it began operating in Nicaragua in 2013.

CSW had warned that religious leaders defending human rights or speaking critically of the government can face violence and arbitrary detention. But Hancock and Orozco said their church never engaged in political discourse.

While maintaining good relations with officials, Mountain Gateway developed fair-trade coffee practices and offered disaster relief to families affected by hurricanes.

By the time Orozco was arrested, his church had hosted mass evangelism campaigns in eight Nicaraguan cities, including Managua, where 230,000 people gathered with the government’s approval in November 2023.

An unexpected imprisonment

Orozco and 12 other members of Mountain Gateway were arrested the next month.

“They chained us hand and foot as if we were high-risk inmates,” he recalled. “None of us heard from our families for nine months.”

The prison where he was taken hosted around 7,000 inmates, but the cells where the pastors were held were isolated from the others.

The charges they faced weren’t clarified until their trial began three months later. No information was provided to their relatives, who desperately visited police stations and prisons asking about their whereabouts.

“We still had faith this was all a confusion and everything would come to light,” Orozco said.

“But they sentenced us to the maximum penalty of 12 years and were ordered to pay $84 million without a right to appeal.”

Preaching in prison

Fasting and prayer helped him endure prison conditions. Pastors weren’t given drinking water or Bibles, but his faith kept him strong.

“The greatest war I’ve fought in my Christian life was the mental battle I led in that place,” Orozco recalled.

Guards didn’t prevent pastors from preaching, so they ministered to each other. According to the pastor, they were mocked, but when they were released, a lesson came through.

“That helped them see that God performed miracles,” he said. “We always told them: Someday we’ll leave this place.”

Molina said that several faith leaders who fled Nicaragua have encountered barriers imposed by countries unprepared to address their situation. According to the testimonies she gathered, priests have struggled to relocate and minister, because passports are impossible to obtain, and foreign parishes require documents that they can’t request.

But Orozco fared differently. He shares his testimony during the services he leads in Texas, where he tries to rebuild his life.

“I arrived in the United States just like God told me,” the pastor said. “So I always tell people: ‘If God could perform such a miracle for me, he could do it for you too.’”

Laymen were targets too

Onboard the plane taking Orozco to Guatemala was Francisco Arteaga, a Catholic layman imprisoned in June 2024 for voicing his concerns over Ortega’s restrictions on religious freedom.

“After 2018, when the protests erupted, I started denouncing the abuses occurring at the churches,” Arteaga said. “For example, police sieges on the parks in front of the parishes.”

Initially, he relied on Facebook posts, but later he joined a network of Nicaraguans who documented violations of religious freedom throughout the country.

“We did not limit ourselves to a single religious aspect,” said Arteaga, whose personal devices were hacked and monitored by the government. “We documented the prohibitions imposed on processions, the fees charged at church entrances and restrictions required inside the sanctuaries.”

Arteaga witnessed how police officers detained parishioners praying for causes that were regarded as criticism against Ortega.

According to CSW, the government monitors religious activities, putting pressure on leaders to practice self-censorship.

“Preaching about unity or justice or praying for the general situation in the country can be considered criticism of the government and treated as a crime,” said CSW’s latest report.

Building a new life

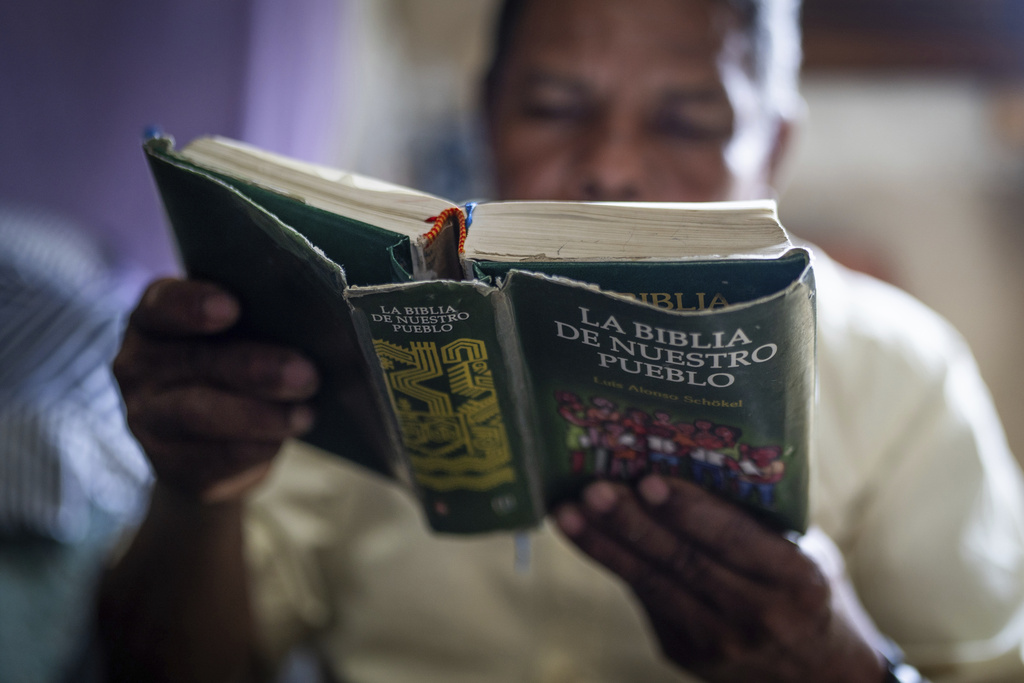

Prison guards also denied a Bible to Arteaga, but an inmate lent him his.

It was hard for him to go through the Scripture, given that his glasses were taken away after his arrest, but he managed to read it back-to-back twice.

“I don’t even know how God granted me the vision to read it,” said Arteaga, who couldn’t access his diabetes medicine during his imprisonment. “That gave me strength.”

He eventually reunited with his wife and children in Guatemala, where he spent months looking for a new home to resettle. He recently arrived in Bilbao, Spain, and though he misses his country, his time in prison shaped his understanding of life.

“I’ve taken on the task, as I promised God in prison, of writing a book about faith,” Arteaga said. “The title will be: ‘Faith is not only believing.’”

____

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.